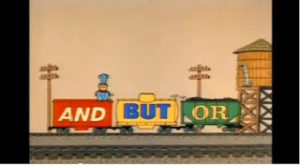

Writing Scenes at the Conjunction Junction

So everyone knows a story needs a beginning, a middle and an end. What a lot of non-writers don’t realize is that the scenes making up a story also have a structure. Each scene has a beginning where a character starts out, a middle where a conflict arises, and an end where the protagonist either come out better in their journey towards the book’s conclusion or worse. And when I’m writing the end of a scene, I’m reminded of the old Schoolhouse Rock song “Conjunction Junction” because my favorite ways to end a scene are “Yes, but” or “No, and“. Get it? And, but, and or will take you pretty far… (You can view the video here if you have no idea what I’m talking about: https://youtu.be/ODGA7ssL-6g). I first heard about the conflict driven “yes, but” and “no, and” during a Writing Excuses podcast (which I can only say good things about—go listen at http://www.writingexcuses.com)

So everyone knows a story needs a beginning, a middle and an end. What a lot of non-writers don’t realize is that the scenes making up a story also have a structure. Each scene has a beginning where a character starts out, a middle where a conflict arises, and an end where the protagonist either come out better in their journey towards the book’s conclusion or worse. And when I’m writing the end of a scene, I’m reminded of the old Schoolhouse Rock song “Conjunction Junction” because my favorite ways to end a scene are “Yes, but” or “No, and“. Get it? And, but, and or will take you pretty far… (You can view the video here if you have no idea what I’m talking about: https://youtu.be/ODGA7ssL-6g). I first heard about the conflict driven “yes, but” and “no, and” during a Writing Excuses podcast (which I can only say good things about—go listen at http://www.writingexcuses.com)

So stepping off of memory lane, if you’ve ever talked to someone who does improvisational comedy, they’ll tell you the first rule onstage is to always continue the scene with a “Yes, and”. Improvisational theater often builds and builds to silly and outrageous heights as each player adds onto the madness of the scene. But as a writer, my stories can’t be so free-form. I don’t want my scenes to go on and on. I want them instead to drive the conflict of my novel. And that’s where the evil opposite of “Yes, and” comes in—“Yes, but.”

“Yes, but” is a common argument your friends use or a rival at work utilizes to shut you down—but in a nice way. It says, “you have a valid idea but it won’t work for us.” And that is conflict gold. It seems like a victory but it’s really not. By employing a “yes, but” as the result of a scene your character thinks they’ve won against the villain but there are consequences—and if you’re a good writer, those consequences have made matters worse. For example, the hero leaves the safety of his family’s house to rescue his love interest from a horde of zombies. He saves his love interest, but as a direct consequence of his actions, his mother and father are down a defender for the family home and when the evil villain sends his trained werewolves to break in during the distraction of the zombie attack, his parents are captured.

Okay, that’s a silly example, but you get the idea. As a direct consequence of the hero’s actions, he both wins and loses. This is great on the characterization front. It gives a character backstory for future decisions encouraging him to question his own judgement. It shows that the character made a choice and demonstrated that all choices have consequences. These are key ways of engendering empathy from a reader. Readers both identify with choices and will feel a kinship with a character as the story goes on because they shared that moment and know how it turned out for your hero.

Of course, if you want to demoralize your character (something I love to do as we approach the Black Moment in the plot), you can stop giving her any wins at all. That’s where the second option, “No, and” comes in. This is used when you want your character to fail and as a result of the failure things also get worse.

Of course, if you want to demoralize your character (something I love to do as we approach the Black Moment in the plot), you can stop giving her any wins at all. That’s where the second option, “No, and” comes in. This is used when you want your character to fail and as a result of the failure things also get worse.

“No, and” is the worst of all possible outcomes for a scene. In this kind of scene the hero leaves his family home unprotected to rescue his love interest and then arrives to find his love interest bitten by a zombie just as he hacks his way to his lover’s side. Meanwhile, the trained werewolves have also attacked his family home and captured his parents. No, he didn’t save his love interest, and his parents are captured. How will he ever get out of this pickle?

“Yes, but” and “No, and” work to create conflict in a story because they both make for a bad outcome on a scene. And as a writer that’s what you want.

THINGS SHOULD ALWAYS GET WORSE FOR YOUR CHARACTER.

Yes, readers say they want good things to happen to characters, that they want only the best for the heroines and heroes they love. But they really don’t. They want to see your character triumph. They want to watch their favorite hero overcome. They want to the heroine to succeed despite all the odds and all the setbacks. If only good things happen to them—that is boring. Never give a reader what they want because they don’t really want what they say they want.

These small scene failures build and build throughout your book. They sometimes look like successes but because of “but” or “and” they are failures. They make things seem hopeless. Then when all is lost, the character decides they will win or die trying. That’s when the real success happens. That’s when the hero selflessly surrenders himself to the authorities in a desperate gambit to distract them while his love interest escapes. That’s when the heroine makes a last ditch effort to repair the space station knowing she will probably be sucked out into the vacuum of space. That’s when the little woodland animal stands up to the massive backhoe that is tearing down the trees of the forest and realizes they’re too small to be seen by the driver. That’s when your reader gasps and can’t imagine any avenue for their favorite character to escape. And when you shine as a writer because you make sure they do. It is the buildup to the amazing climax of your book.

So if you’re stuck in the middle of your plot and unsure how to punch up a scene, remember to visit Conjunction Junction and make things worse for your character. Make those characters suffer again and again until that final shining moment when they win. Make them earn their happily-ever-after. Your readers will thank you.

[adinserter name=”Amazon”]